Donald (Tana) Cooper's life has been shaped by struggle, survival, and resilience. His journey has been marked by pain, loss, and above all, strength. Through the chaos of his youth, the turmoil of his family’s history, and the brutality of his upbringing, one constant remained: the love of his life, Marama. Their story is not just one of love but of survival - a shared journey through unimaginable suffering and heartache, bound by an unwavering bond and supported by the aroha of the Māori Cancer Kaiarahi Service and Manaaki Manawa - The Cancer Support Group.

Born to a family with deep ties to the land around Russell, my early years were anything but easy. My childhood was marked by violence, neglect, and emotional scars that would stay with me for a lifetime.

My name was given to me by my mother who I never knew, and my father who struggled with his own demons. I was raised by my aunt, “Mum”, a woman who worked hard, and raised her siblings and her nieces and nephews. She was beautiful but she carried the weight of life’s struggles on her shoulders, just like the rest of us.

I hated my name. Donald. It was so embarrassing. It didn’t fit and it made me feel like an outsider.

Especially at school. Kids would taunt me, calling me “Donald Duck,” making duck noises and laughing. I could never escape it. My name alone was a target, and I was never allowed to forget it.

But the worst of my early life came from within my own home. My stepfather’s cruelty and violence left lasting marks on my body. Beaten for no reason other than my existence, I spent years trying to escape the constant cycle of abuse.

It wasn’t just physical punishment - "You little bastard," I would hear repeatedly.

I wasn't great at school, but I was top in swimming, a champion tennis player, the best at cross country, and pretty good at gymnastics. I got beaten up all the time because jealousy was a huge thing. The others couldn’t stand how well I did, so they'd find any excuse to pick on me. But none of that seemed to matter when we left home one day on the bus.

We were off to represent our school in gymnastics in Whangarei, but before we even made it there, something caught my eye. The bus had pulled up near a garage, and as I looked inside, I saw something that made my heart race - a wall full of guns. I couldn't believe it. My cousin leaned over and said, "Let’s come back and steal those guns." I didn’t hesitate, “yes, absolutely!”

We'd come back for the guns, and we figured it was going to be easy. My cousin's dad worked on the railway and had a motorized jigger, and a key. My cousin found two flagons of fuel and, that night, we were off.

We struggled to get the jigger running, but we managed. It wasn't fast, but it was moving. I could've outrun it, probably, but we didn't want to risk it. And then, just as we turned a corner, I saw a light on the hill. I couldn’t believe it – according to my cousin the night train had already passed through, but here it was. We pulled the lever to speed up, but the jigger didn't move fast enough.

The train came at us faster than I expected. I don’t know how we didn’t get hit. I slammed on the brakes, trying to lift the jigger off the tracks. But it was too late. The train was almost on us. The next thing I remember, I dove off the jigger and hit the gravel, scraping my chest. We scrambled, took off in a flash, heart racing, barely escaping with our lives.

We were 15-years-old and neither of us wanted to go back to our lives so we decided to run.

We grabbed some shoes from his place - I had none, just bare feet - and my cousin stole his dad’s .22 rifle. We found a shotgun hanging in another garage, which we stole. From there we spent a week in the bush, living off fresh water crayfish, but the situation turned bad and we both ended up with Diahorrea. We left the bush and headed for a nearby town, where we stayed under some piles of timber, trying to stay out of sight. The last thing we wanted was to be caught and sent back home.

One morning, we heard machinery, and the timber was being lifted. We took off, nervous, knowing we had to keep moving.

We talked a milk truck driver into buying the shotgun from us. We told him my dad had given it to me for my birthday. The man actually believed us, and for a minute, it seemed like we had it made. He gave us £5 (pound) for the gun. That was all we needed to get a bus ticket.

Catching the bus was the plan but first we decided to treat ourselves to an ice-cream and a milkshake from a Tip Top shop - we hadn’t eaten in days - and then it all fell apart. A big guy came into the shop, blocking the door. He started yelling, swearing, saying we were caught. I was ready to fight. I moved toward him, but before I could do anything, the place lit up with police lights.

Cops were everywhere.

They took us to the police station. My cousin’s dad came, took him, and called us mongrels. I stayed half the night until my brother came and got me. My stepfather was furious when I got home. He yelled at me and started telling me I had to settle down and go back to school.

He grabbed the broom, trying to intimidate me. But I wasn’t scared anymore. I grabbed the broom out of his hands and broke it in half. “What are you gonna use now?” I said, daring him to do something. My mum came out, but I never answered to her. She told me to go to bed, and I did – a double bed with six of us sleeping it in and only one blanket.

I decided I had had enough and soon after I ran away. Again.

My cousin Betty, who I considered more like a sister, had met a man in Invercargill and was flying down to be with him. I followed, staying with

them for a week, but her partner didn’t like me and kicked me out. Betty then took me to Berrington Heights, which I would call home for the next few years. I worked as a carpet layer, a bar manager, an oyster opener, a hamburger maker, and a shift worker at Tiwai.

During my time at Tiwai, around 1969, I met my first wife. We married and moved to Tuatapere, where I began working in logging. The work was tough, demanding, but I thrived. Soon, I was a contractor, managing two logging gangs. My wife and I had three children, and for the first time in my life, I thought I had finally made it.

But life has a way of throwing curveballs when you least expect them. The years of hard labour began to take their toll on my body. The doctor told me I had to stop logging or I would end up in a wheelchair. My marriage also fell apart, and with no other option, I left everything behind.

I bought a property in Makarewa and planted potatoes. Even then, things weren’t easy. I met another woman, but that didn’t work out either, and I ended up moving into a cabin at the Oreti Beach Camping Ground. I was trying to figure things out and get my life back on track.

And I did. One day, I came across an ad in the newspaper for a youth worker role in drug and alcohol rehabilitation. Though I had no experience, I felt it was a great opportunity. My colleague was a beautiful woman named Marama, who would end up changing my life.

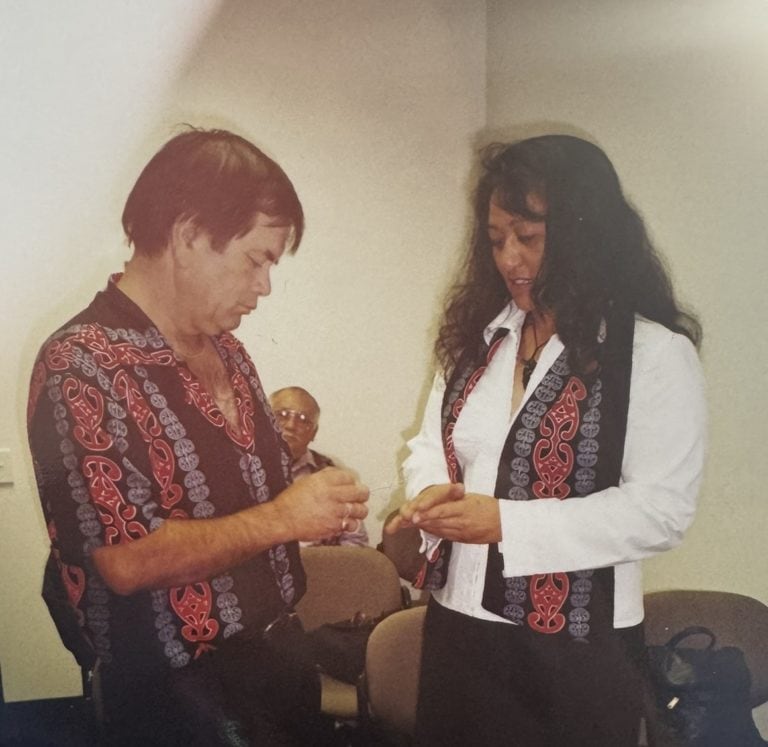

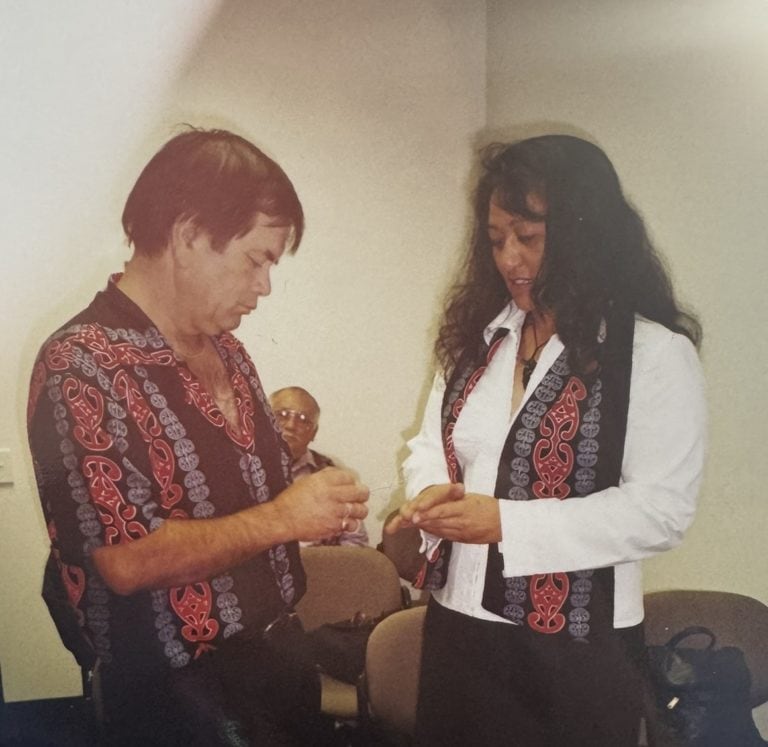

When I first met her, I didn’t know the depth of what was to come. She was beautiful, smart, strong -everything I admired in a woman. We didn’t rush into things. Our relationship grew slowly, carefully, but the connection was undeniable. However, Marama carried a weight no one could have predicted. We weren’t just partners in love; we became partners in survival.

Soon after we married, Marama was diagnosed with a rare, aggressive form of cancer. It began at the base of her spine, slowly eating away at her bones. The pain she endured was unbearable, and she lost the ability to feel her legs. It wasn’t just the cancer - it was the helplessness we both felt as we watched her deteriorate.

For the next 16 years, I became her caregiver. I was there for every doctor’s appointment, every struggle. Her body deteriorated, and she could no longer walk. Every day was a battle. Some days, she’d feel a little stronger, but most days were filled with pain and exhaustion.

In her final years, our relationship changed. The cancer had taken so much from us physically and emotionally. Yet, our bond was built on more than just moments of joy - it was forged in the hardest of times. Even when we could no longer do the things we loved together, our love remained solid, enduring.

In her final weeks, she fought with everything she had to stay with me, but the disease won. Her passing left a hole in my heart that will never be filled. I miss her every day.

Her death didn’t break me, but it changed me. It made me realize how fragile life is, how fleeting our time with those we love. But it also taught me about resilience. Even in the face of unbearable pain and loss, we continue moving forward. And that’s what Marama would have wanted. She fought till the end, and I will too.

Not long after she passed, I was hunting deer with my brother. I hung the deer up in my shed and, after boning them, I came inside feeling unwell. I started throwing up and I collapsed on the couch. I woke up to find my living room full of medical people. I was rushed to Southland Hospital, and later transferred to Dunedin, where it was revealed I had cancer too.

In Dunedin, I had surgery to remove my spleen, pancreas and part of my liver.

That was 18 months ago. I was strong back then, but now, I’m just skin and bones. I chose not to undergo chemotherapy. For me, the battle with cancer was as much emotional and spiritual as it was physical. I knew I had to find other ways to fight.

Through it all, the Cancer Kaimahi were there, offering practical assistance and emotional support. They brought me food for Christmas, which meant more to me than I can express. It was hard for me to accept help, as I’ve always been a giver, but their kindness reminded me that it’s okay to lean on others when you need it.

The Cancer Support Group, Manaaki Manawa, has also been a true blessing. I come often to help others, but they are always there for me too. It’s a place where we share our fears, hopes, and triumphs. I know I can reach out to them whenever I need support.

The cancer is gone now, which I’m incredibly thankful for, but life still feels heavy. I miss my wife every single day. There’s an emptiness that I don’t think will ever go away. But through all of this, I’ve learned that life goes on. It’s how you choose to live it that matters. I keep busy. I always have something to do.

No matter how hard it gets, you can’t kill a weed! I’m still here, and I’ll keep fighting, just like I always have. There’s still so much to do, and I’m not done yet. The support of the Manaaki Manawa and the Cancer Kaimahi is a big part of why I’m still here. I’m forever grateful for their unwavering support. They’re a reminder that even in the darkest moments, you’re never alone.